Click

for Site Directory

Click

for Site Directory2050056 Leading Aircraftwoman Hilda Mudd

Hilda was born in Estevan, Saskatchewan, Canada in 1923. Her parents and her uncle Absalom emigrated there from Grassingtonin Yorkshire and set up a smallholding on the prairie. Her father suffered from pernicious anaemia (where the body can't process vitamin B),

and in those days there was no effective treatment for it, so he died when she was only 6 years old.

Hilda and parents, and Uncle Abe at Kincade Farm in Canada

Hilda and Uncle Abe

ride in style

and speaking with a funny foreign accent she did not make many friends at school. But as with many of her generation she left school at 14

and went to work in a grocers' shop.

When war came she joined the W.A.A.F.s as soon as she was able, and at last she found herself able to make friends and fit in. She also go totravel around the UK and meet lots of people. They were the best days of her life, she said.

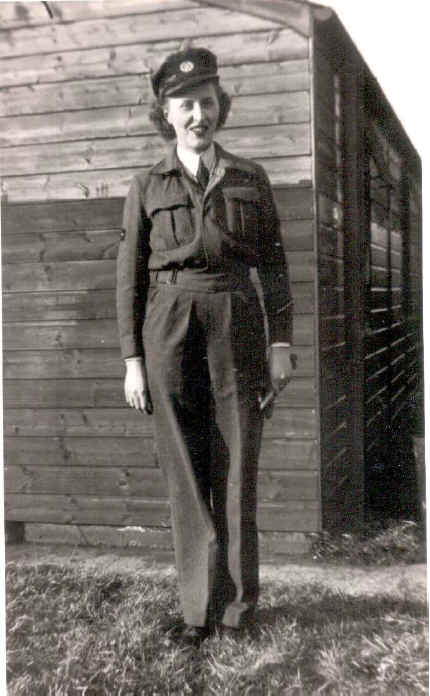

2050056 Leading Aircraft Woman Hilda Mudd .

Hilda in 1941 on her 18th birthday

This is the story of Hilda Harrison (Nee Mudd) who served with 953 Squadron at Barry

Her service number

indicates she joined up around

May

1941 by the Inspector of Recruiting.

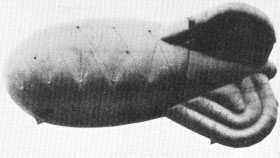

"Life on

a barrage balloon site was totally different from that of an R.A.F. station. We

were a self-contained unit of 14 to 16 young

girls. I was

18 when I did my training in the

and around

ports and cities around

arduous work

and what is now called "antisocial hours"; starting at 2/4d per day for

Aircraftwoman 2nd Class, plus 4d per day War

Pay.

We were allowed one 24 hour pass each week, and two evening passes, weather

permitting. Every night, we stood picket duty

on 2 hour

shifts. We lived in Nissen huts . those half-moon corrugated iron contraptions;

cold in winter, hot in summer. The floors

were

usually bare concrete with a bedside mat. We kept our clothes in empty

ammunition boxes. Sites near the centre of the city

would have

electric lights. Those not so lucky would have Tilley lamps. Our water came from

a stand-pipe in the ablutions hut,

although some

sites might have to use one several hundred yards away. There were no baths, of

course. Twice a week we went

in pairs to

the public baths, usually a bus-ride away. On one site I was stationed on in

Barry Dockyard we took the train to have

our bath".

Barry Island postcard sent by Hilda to her mother: the "X" marks the spot where the Balloon Barrage was set up in WWII.

"All the hot water required on site had to be heated by coke fires. We were

not issued with any coal or kindling wood

and

used cleaning rags soaked in dirty sump-oil from the winch to get our fires

going. If we happened to be near a railway we

were

lucky, as firemen on the steam engines could often be persuaded to throw us a

cob of coal. The toilets were wooden

seats over

iron buckets. Once a week, a tanker arrived and we took turns to empty the

buckets. We had a rota for duty cook also.

It

was important never to allow the kitchen stove to go out, otherwise it would

never get hot enough to cook the next meal.

When the

ration truck came we ate well enough, then meals tended to get skimpy until its

next visit. The meat would be sausages

or offal.

Scrambled dried egg and tinned pilchards also featured largely on our menu. The

puddings were invariably prunes and

custard or

rice. We were issued with 7lb tins of jam for teas and fried jam sandwiches were

a popular delicacy. Sometimes there

was

a slab of cake with the appearance of compressed sawdust which we referred to as

"yellow peril"! There was always a slab of

yellow cheese

with the texture of common washing soap and the milk was tinned. I spent one

Christmas on a training site taking a

trade

test for a promotion. We had one chicken between 22 of us and we boiled the

Christmas pudding in the fire bucket!

That site was

in a park and the stand-pipe was some distance away. To wash, we put on gumboots

and waded into the nearby stream.

Some

mornings we had to break the ice first, but as we were only there for a

fortnight it did not worry us too much. The work was

heavy

and the living conditions were rough but as a consequence the discipline on a

balloon site was pretty easy-going. We did not

have to stack

our beds like they did on a Station. If we had been up most of a stormy night,

attending to a balloon that wanted to take

off on its

own we were allowed a nap during the afternoon. We did not have to wear a collar

and tie. We wore battledress or dungarees

and men's

boots or gumboots and sleeveless leather jerkins in winter. We wore a beret

instead of the usual peaked cap. This was

more

practical for crawling under and around a pitching and tossing balloon on its

bed. One of the things to be carefully guarded against

in

those days of severe petrol rationing was getting the tank of our winch syphoned

in the blackout. The sites still crewed by airmen were

guarded with

a rifle but we girls only had a truncheon to protect ourselves and government

property. I do know of at least one intruder

who

found himself in hospital after sampling the weight of a W.A.A.F.'s

truncheon. The

duty officer often paid a visit in the small hours".

Hilda at Sutton Coldfield 1947

"One Flight

Commander I recall drove a very noisy little open-topped car which could be

heard a mile away on the still night air. He at

least never

caught the guard making cocoa in the kitchen! In some places we were quite an

attraction and would often have an audience

when

we were handling a balloon. One such place was Barry Dockyard where the seamen,

mostly American, would reward our efforts

by

throwing oranges and lemons over the high mesh fence. These were a great luxury

in wartime, although once I was the

receiver of a

bottle of scarlet nail varnish . totally useless to any of us. Apart from not

being allowed to wear it, we all had ugly hands,

scarred

by rope burns and ingrained with oil from handling pulleys and shackles. There

were idyllic summer days when the barrage floated

5,000

ft above us and we lounged in the sun splicing new guy ropes, but also there

were stormy days and nights when we had little rest as

we struggled

to keep our balloon on its storm mooring. To achieve this the bow must always be

kept into the wind . Not easy in a gusting,

veering wind.

Each guy rope had to be moved in turn, one point at a time, whilst another girl

dragged its 56lb concrete ballast block with it.

As the

balloon pitched and tossed in the wind the guy ropes sprang taut and the ballast

blocks swung into the air, just at the right height to

smash a

kneecap, if you did not stay alert. Finally the great silver hulk was edged back

into wind, perhaps only to repeat the process one hour

later

when the direction of the wind changed yet again. To be woken by the duty picket

shouting "Out of wind!", it was not a welcome sound.

It was also

important that the balloon did not rip her belly on her concrete bed or on her

own wire rigging, because she was only made of

Egyptian

cotton covered in silver dope. To this end, we crawled on hands and knees to

adjust the heavy canvass ground sheets under her. It

was important

too that we did not get entangled in the shifting wire rigging. In the blackout

we worked by torchlight, often cold, wet and weary.

Sometimes we

lost the battle to save our charge from destruction. I recall one such winter

night in

A

straining guy rope tore a starboard panel clean out of our out-of-wind balloon,

she then floundered like a wounded elephant until all the

hydrogen had

escaped. That was a lot of wasted gas, and we were not very popular with Flight

Headquarters! However, that was not the only

loss that

night. It was the worst storm I remember. The next day when the wind abated, as

it curiously often did at dawn, the gas trailer arrived

and we had

the tiresome job of inflating a new balloon. We wore plimsolls and no metal

about us, for fear of a spark igniting the highly

inflammable

hydrogen. It was a cold job unscrewing the caps on the huge cylinders. As soon

as the gas began to flow down the hoses everything

became

covered in frost. A damaged balloon was not the only occasion when we had this

task. The purity of the hydrogen had to be carefully

checked daily

and a cylinder or two might be added, but eventually the purity became

dangerously low as it became contaminated by air.

Then the

balloon had to be deflated and filled with fresh gas. This usually happened in

warm weather when the balloon was flying all day.

The gas

expanded at altitude and constantly valved off. In the cool of evening the gas

contracted and a very flabby object hung in the sky above us!

I never heard

of a barrage balloon bringing down an aircraft. They were supposed to do this by

means of a mechanism which cut the steel cable

if

it was fouled, whereupon the cable would wrap itself round the aircraft. But the

balloons did keep enemy bombers at height, when bomb sights

were less

sophisticated than they are today. A silver barrage balloon floating in a sunset

sky had a curious proud beauty all of its own. At W.A.A.F.

reunions

after the war the Balloon Operators always seemed to congregate together even

though they did not know each other in service days.

We were still a trade all of our own."

recruited a lot of his staff from ex-servicemen and women. She worked in the booking office. Some time in the 1950s she moved to Preston,

where she lived in lodgings and worked at the Motor Tax office there. Although she had learned to drive a winch truck during her days in the

W.A.A.F. she never learned to drive a car herself. It was in Preston that she met her husband Tom Harrison, a painter and decorator. He had come

to paint her landlady's lounge. They were married in 1953 and lived all their married life in a house in a village just outside Preston. They had 2

children, Lorna and Graham.

Hilda Harrison passed

away in 2009, on the day before her 86th birthday.

What a delightful tale by a woman who in just a few pages summarized her war experiences with a very descriptive flair.

We as a nation must thank people like Hilda for their service against the Nazi threats during World War II. Without the efforts

put in by people like her this world would have been a very different place. Thank you for your service to the Nation.